Inclusive Design: Environment, Language and Belonging

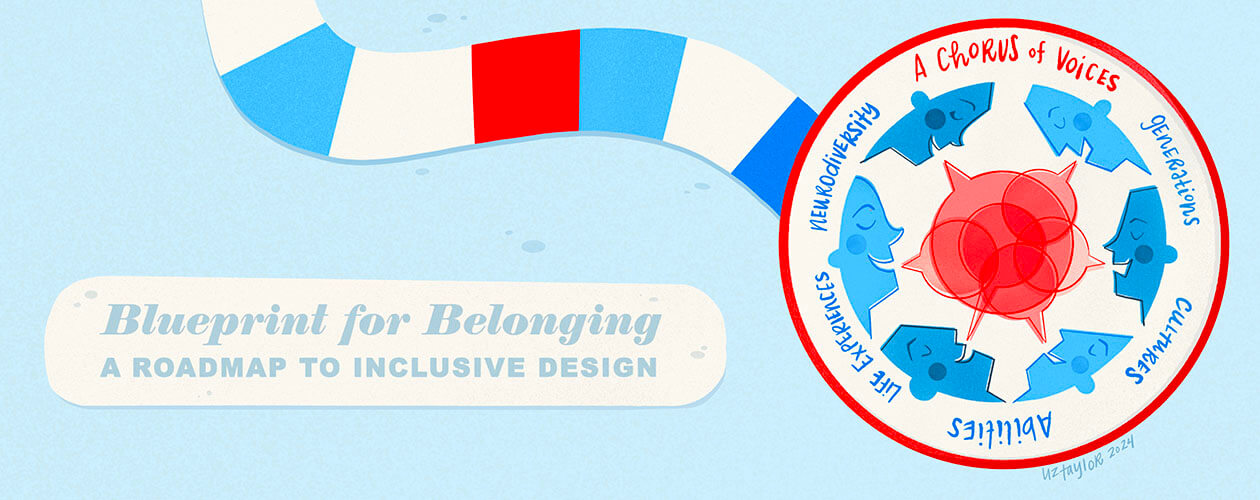

RSP’s Liz Taylor examines inclusive design and the convergence of graphic design, interiors and language to bring communities together and heighten their sense of belonging.

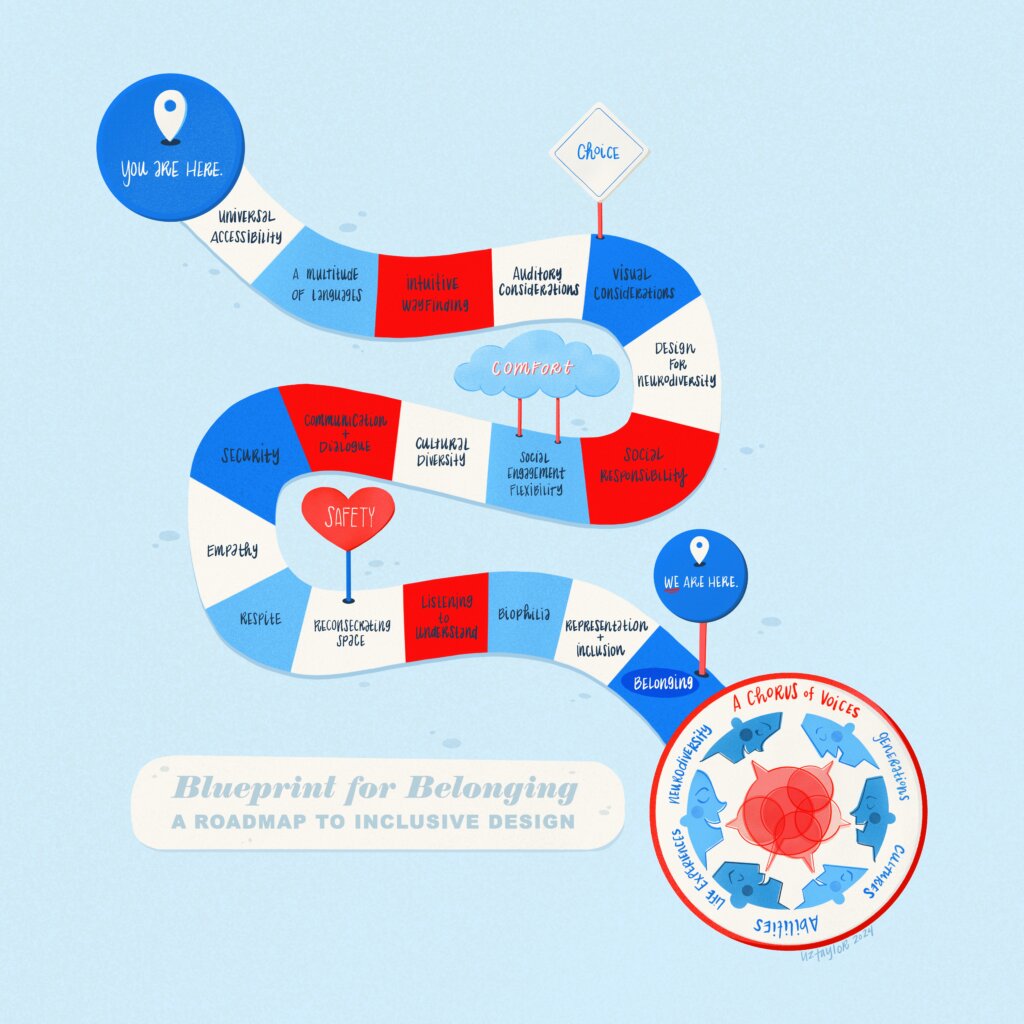

The idea of belonging is foundational to experiential design. It defines my work on every project, both professional and personal. Ultimately, we want to include more people, but also deeply speak to different communities and give them an experience that immediately signals that they belong—that they are in the right place.

When the Design School at Arizona State University approached a number of local designers about a lecture series, Designing with the Desert, this idea of belonging immediately came to mind. Ostensibly, the idea for the lecture series was about working with the desert biome in terms of passive heating and cooling and other sustainable architecture strategies. But for me, as someone who works at the convergence of interior design, graphic design, illustration and architecture, designing with the desert means designing for people and with people, because the desert belongs to all of us.

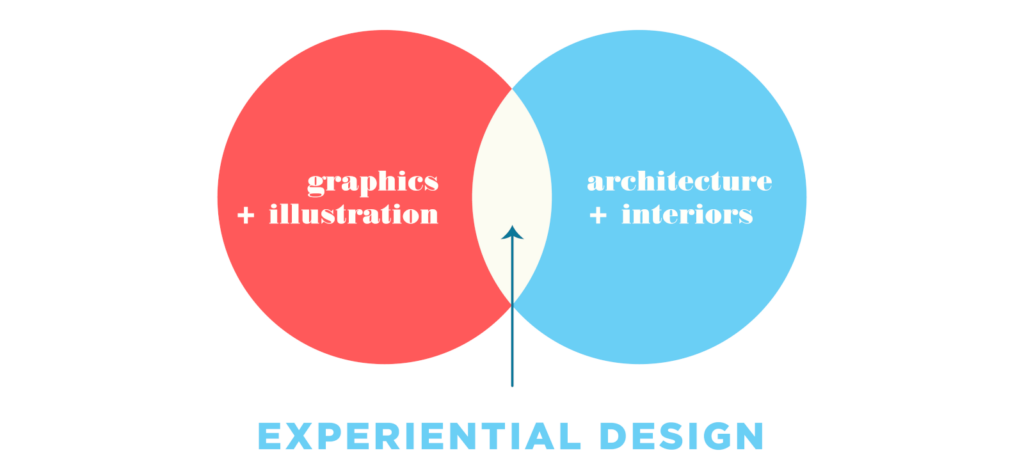

My work includes exhibit design, multi-media and interactive design, civic art, branded environments and of course, signage and wayfinding. I like to think of it as adding a layer of information and storytelling to spaces. This often means relying on “language” (used in its broadest sense), and the choice of that language—the “words” that I use—makes a fundamental difference to how people experience where they are.

You Are Here. I am Here. We Are Here.

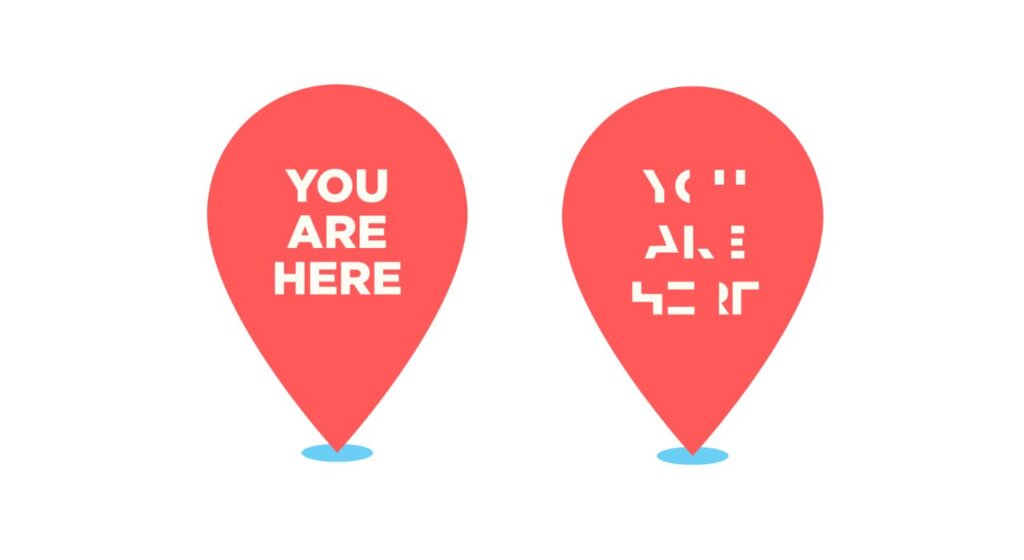

I spend probably too much time thinking about language—I often fall prey to the chronic designer’s curse of over-thinking things. A lot of what I do is messaging within spaces, so I make sure we’re choosing the right words and that those words are landing the way we intend. This stems from growing up as a struggling reader. To help myself understand language better, and root out the intended meaning of things, I associated the letters with characters. This led me to study the visual design side of language.

When my son was identified as dyslexic, I realized that he was simply not accommodated in most places, especially in a world of hyper-media where information comes at us fast and furious. Even the simple task of orienting himself through wayfinding or on a map was a challenge. For more than half of his life, he was in a place of otherness—on the outside of written language. The idea of the quintessential “You Are Here” pin on a map was useless for him, although it is fundamental to what I do. It is immediately recognizable by so many, but totally inaccessible to my son and others like him. So, I looked for ways to convey meaning and message in different ways.

We can only be experts in our own stories, and this area has truly shaped my perspective and sensibility as a designer.

Inclusion versus Belonging

We talk a lot about inclusion these days. I can do a lot of things to include you, but that doesn’t mean you truly feel a sense of belonging. At my house, “belonging” looks like my husband painstakingly reading every subtitle in a foreign film that my then-9-year-old film buff son was desperate to watch (Ladri di biciclette, or The Bicycle Thief, for those keeping track).

In another film example, Manuelito Wheeler lobbied Lucas film for 16 years to get Star Wars: A New Hope dubbed in Navajo with Navajo voice actors. The community came out. A Hopi artist created an R2D2 art piece with Hopi symbols. Language is a vessel for concepts and by hearing this story in their language, the community can join in that shared experience and culture. There is common ground here that transcends cultures; it’s a story that belongs to everyone.

More recently, Lily Gladstone started her 2024 Golden Globes acceptance speech in her Blackfoot native language and in doing so, brought her entire community on stage with her.

Instead of making people feel that they’re merely allowed to be in a space, we are doing more to make people know that they belong there. They are included just the way they are. The space has adapted to them and not the other way around.

Getting Everyone to the Trans-Disciplinary Experience of Design

As designers, it’s sometimes hard to know where to start. How to understand community, multiple perspectives, and how design will impact people. We want a trans-disciplinary experience, not just interdisciplinary.

When we’re creating a space for belonging, we start by identifying and bringing in the specialists. Every project is a new learning opportunity, but we can’t know everything. Part of our job is knowing what we don’t know and reaching out to the right people. I want to see architects and designers build teams that look more like a series of overlapping circles—a co-op or collaborative of talent. What if we included writers, people who speak different languages or various cultural experts? Maybe an archeologist or a musician or an artist?

As designers, we become too comfortable when we stand shoulder to shoulder facing in using the language of design, which itself can be exclusive. If we stand shoulder to shoulder facing outward, we will begin to see others who should be a part of the conversation. True diversity of teams is what will build a sense of belonging, brick by brick.

Inclusive Design Elements

Some elements of inclusion are already commonplace, like braille on regulatory signs and instructions in multiple languages. But we have to keep moving in the right direction, looking at not just multiple languages but auditory experiences and cultural nuances. That might look like a street sign renamed on native land to reflect the language of the people. Or a museum exhibit that, instead of just having a translation, has two experiences that are equally powerful and informative in different languages. Or even a simple land acknowledgement that can move us toward the concept of the duality of space that ideally includes or integrates the heritage of the land.

At our best, our work is designing for everyone, for different abilities and all the different experiences we can think of, and perhaps those we don’t yet know or understand. We need to expand beyond the letter of the ADA to incorporate all the new research coming out about neuroscience. We are going to see more research and information on brain science in the next 50 years than we’ve seen in the entirety of human history, and it will impact everything—how we work, how we treat each other, and how we design.

Inclusive Design Means Dignity for All

We have all seen examples of inclusive design in the real world, but if it wasn’t “for us,” we may not have noticed. I worked on a children’s hospital that had a lot of inclusive and experiential design elements for the patients, but adults likely didn’t pick up on it right away.

At this hospital, the staff worked with prenatal patients all the way up until age 23. My overarching concept was that everyone should be able to navigate the space with dignity. I have a soft spot for pre-readers, so our team used a lot of illustration to help even the littlest kids navigate without reading a single word. This project integrates all sorts of intuitive wayfinding. Each floor has a different color and a different animal, so patients immediately know if they’re in the right place, as soon as the doors open. Illustrations, like a frog jumping toward the elevator, give directions without relying on the written word.

The more we spoke to parents, the more we realized that this hospital is a home for the patients. For some of them, it’s their last home. We wanted to give them a way to navigate with dignity and give them at least a small sense of storybook magic. To give them a sense of belonging that supersedes how scary a hospital might feel.

The Experience of Language and Belonging

My husband and I are both advocates in the dyslexia space and we have learned a lot since our son was diagnosed. One major concept that sometimes gets lost is that the strategies that help dyslexic kids learn how to read work for all kids. This is similar to the idea that the design strategies that benefit the neurodivergent community are actually good for everyone. But many of the reading strategies that school systems have implemented in recent years only work for kids who would have figured out how to read regardless of the teaching methods used.

That’s why my husband and I were part of a coalition that successfully lobbied to pass a dyslexia law in Arizona that formalizes the definition of dyslexia and provides grants for dyslexia training for teachers. I illustrated a book about dyslexia that helps parents navigate the school system and get support for themselves and their children. If more people understand these ideas, the more inclusive school can be for every child.

Next Steps for Inclusive Design

We have a lot more work to do. Our work with ASU and other universities gives us unique insight and opportunities to break out of traditional design modes and increase inclusion for young people in our community who are just starting out in the world. But truly, every project gives us the chance to take the concepts of language, belonging and inclusivity and put them into action—to create real-world examples of how we can dissolve existing boundaries and help more people feel that they truly belong.