Medical Assistance

by Amy Goetzman, Architecture MN

Originally published November/December 2016 Issue

The American Refugee Committee teams with RSP Architects to create a replicable healthcare clinic for communities in need half a world away.

Imagine designing a public building for a part of the world with no building codes and little infrastructure. The site lies in a conflict zone, the budget is next to nothing, and you can’t use any building materials that are expensive, heavy or otherwise difficult to transport. Oh, and you need to equip the building to deliver healthcare services.

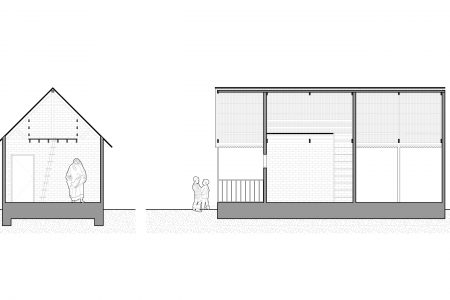

RSP Architects met this particular challenge with a replicable prototype for a new clinic that is now in service in Karambi, on the eastern edge of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The architects conceived the building in partnership with the Minneapolis-headquartered American Refugee Committee (ARC), which is developing health, agriculture, and clean-water initiative called Asili.

Asili, which means “foundation” in Swahili, is helping the country recover from a decades-long civil war that destroyed much of the region’s limited civic infrastructure. ARC, led by CEO Daniel Wordsworth, developed the Asili model to put local residents in charge of the basics, rather than have them rely indefinitely on outside help. With a plan for sustainable agriculture, clean water (brought in by pipeline), and high-quality healthcare, Asili has already spurred new business development in the community.

‘We were blown away by the need for this project,” says RSP design principal Derek McCallum, AIA. “We designed a very simple structure, but it enables local healthcare professionals to provide essential care services in an area where people have very few options.” The clinic will soon be replicated in the nearby community of Mudaka.

The basic design took shape over a five-week period, during which the architects worked under very limited guidelines. The main imperative: Create something a bit nicer than an earlier prototype, which was built from a decommissioned shipping container.

“The first clinic had some problems in terms of transportation and functionality, but it also lacked a welcoming and professional presence.” McCallum continues. “Our challenge was to design something here that could be built there and repeated where needed, in the middle of the jungle if need be, using materials that could be affordably sourced nearby. We also wanted the clinic to feel like a clinic – clean, professional, attractive, and welcoming.”

The building, which features a pharmacy, exam rooms, and a minor surgical area, is primarily constructed of local materials. Asili-brand color and decorative details give it a warm, familiar look to the local community. Patients come to receive care for malaria, malnutrition and diarrhea – treatable and preventable conditions that kill 20 percent of young children in the region every year. Patients can also access clean water from the site.

“RSP greatly increased the utility of the building,” says Wordsworth. “The new design allowed us to increase the efficiency of our daily clinic operations. New functionality included the ability to have a retail space for over-the-counter medicines and multiple consultation rooms that allow us to see patients much more quickly.”

RSP designs healthcare facilities for large U.S. providers, so this clinic represented a dramatic scaling down – except in one area, which needed to be scaled up.

“In the U.S., a person goes alone, or maybe with one other person, when they visit the doctor,” McCallum explains. “In the Congo, an entire family accompanies a sick person to the clinic. There is a cultural difference we had to understand in our design. So we have what might seem like a disproportionately large waiting area. This helps the community feel like the clinic belongs to their world, rather than something that was created elsewhere and dropped into place.” AMN